“Everything Everywhere All At Once” is Out Now on Streaming, Blu-ray, DVD, and Digital

Directed by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, collectively known as Daniels, the film is a hilarious and big-hearted sci-fi action adventure about an exhausted Chinese American woman (Michelle Yeoh) who can’t seem to finish her taxes.

About The Film

Purchase the movie now via my affiliate link on Amazon.

Sitting on a wall in director Daniel Kwan’s back office in Los Angeles’s Highland Park is a framed work by the artist Ikeda Manabu, “History of Rise and Fall,” an elaborate pen-and-ink drawing featuring a maelstrom of pagodas, gnarled cherry branches, and railroad tracks—a fittingly abundant example of Manabu’s glorious, almost painfully maximalist style.

“He does these things that hurt your brain when you look at them because they’re so intricate, so detailed, so dense,” Kwan explains. “But when you pull back, you’re like, oh, that’s a tree.” Kwan and his filmmaking partner, Daniel Scheinert—the auteur duo otherwise known as Daniels—needed to find their tree. This was circa 2016, when they were first outlining what would become Everything Everywhere All At Once, a project that was beginning to increasingly resemble the zoomed-in chaos of a Manabu piece. In a photo they took from that time, a headache-inducing diagram on a wall-sized chalkboard contains over a dozen color-coded storylines, scribbles of percolating ideas, and what may or may not be a phallic doodle (or Chekhov’s gun).

At the time, Kwan was worried that the movie he was working on was just too much. It’s an entirely predictable issue—one written into the title of the movie—that also happens to be what makes the film feel genuinely singular and even, as its cacophony of elements clarifies into something startlingly simple, rather transcendent. Watching the finished film today, it retains that sense of maximalist, gonzo energy, and even now, having sorted it all out, the directors still chuckle to each other about how to describe exactly what their movie is.

“There’s the family drama answer and the sci-fi answer and the philosophy answer,” Scheinert says. Or you could say it’s a kung-fu flick that hops around multidimensional universes, with Michelle Yeoh as a reluctant savior figure at its center. There’s the answer about generational divides and the internet and the latent dread endemic to living in the modern age.

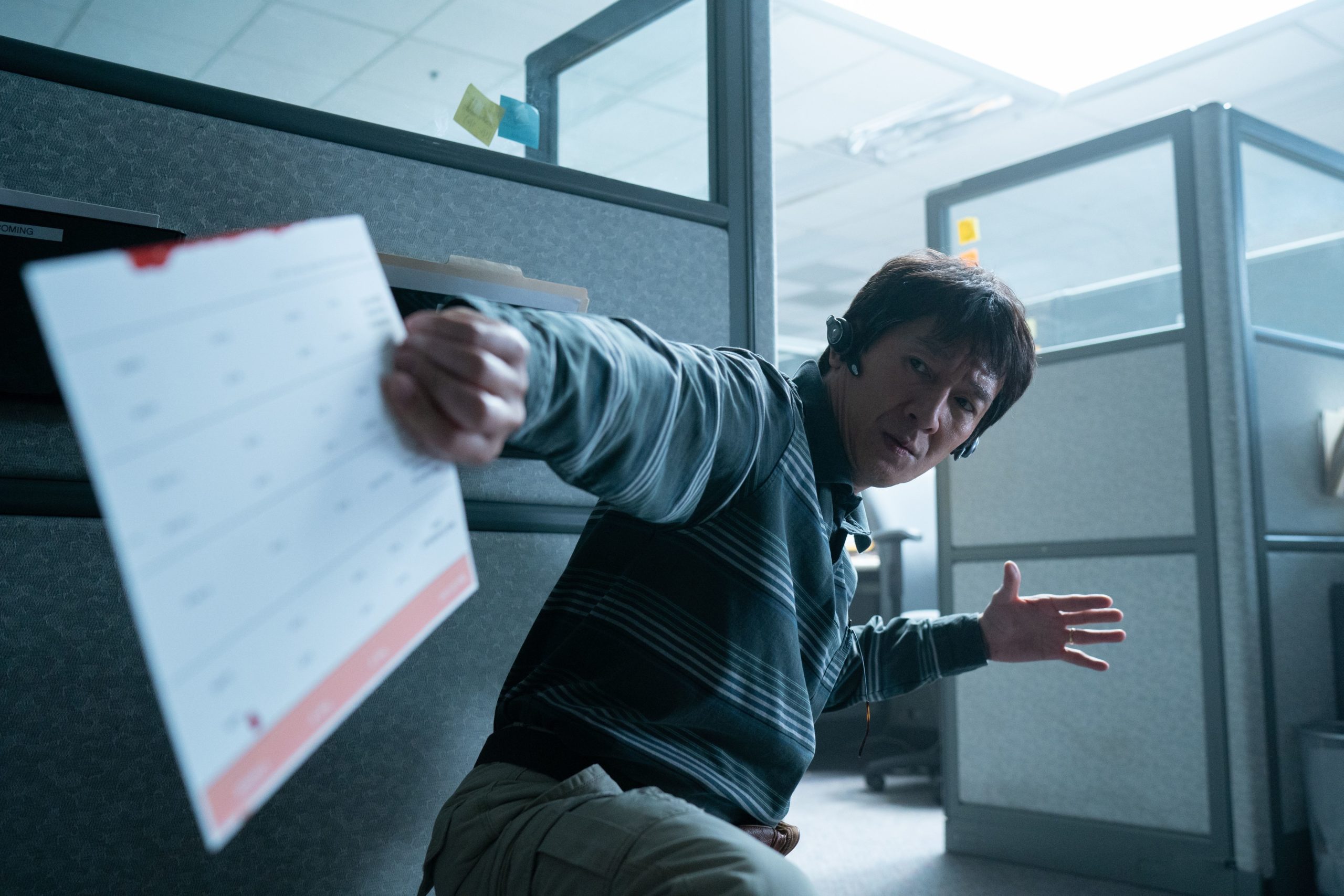

There’s also the early logline that Daniels wrote themselves: a movie simply about a woman trying to do her taxes. It’s not exactly wrong—it is, after all, where Everything begins. When the film opens, we meet Evelyn Wang (Yeoh) as a harried laundromat owner, living above her business in a cramped apartment and facing a mountain of paperwork amid an audit from the IRS. She is stressed about her aging father (James Hong) coming to stay and struggles to listen to both her grown daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu) and her tender-hearted husband Waymond (Ke Huy Quan). But while meeting with an IRS agent (Jamie Lee Curtis), a strange occurrence involving her own husband pulls her into a multidimensional adventure that puts the fate of every universe in her hands—and also forces her to confront who she is to herself and her family.

Arriving at that last part is the moment when Daniels took a step back and finally saw the tree. “We could say a million things about it, but the most simple, honest thing is it’s about a mom learning to pay attention to her family in the chaos,” says Kwan. The film, as with Daniels’ previous work (Swiss Army Man, the iconic music video for Lil Jon’s “Turn Down for What”), rushes headlong into unruly anarchy: Evelyn is plunged into the metaphysical world of “verse-jumping,” veering from the mundane dreariness of an IRS building to the palatial lair of a nihilistic villain named Jobu Tupaki, from the flashing lights of Hong Kong red carpets to a deserted canyon where sentient rocks manage to have a heart-to-heart. But this sense of an unhinged imagination, of endless mayhem, ultimately serves to transform the universal, or the multi-universal, into something intimate—an earnest meditation on truly seeing those near us in a time when it feels as if the center will not hold.

“The biggest seed that drove us through, that felt like a metaphor for what we’re going through right now in society, is just this information overload, this stretching,” Kwan says. “People

keep saying ‘empathy fatigue’ set in with covid, but I feel like even before covid we were already there—there’s too much to care about and everyone’s lost the thread. That was the last key, turning this into a movie about empathy in the chaos.”

The film slyly tweaks the ‘hero’s journey’ story beats that audiences have come to expect, squishing and stretching a three-act structure as if the movie itself were jumping through a fracturing multiverse. That sense of infinity—all of the possible worlds, the depthless rabbit holes, all of the tiny moving pieces underneath it—stayed front of mind for the co-directors as they got a grasp on the nuts and bolts of the film’s story; it felt crucial that people watching the movie could feel the same sense of vertigo that Evelyn does, that sense of being overwhelmed by the noise and splintering choices of all of her lives. The bold structural gambits were key to creating that experience.

The film’s thematic heart helped Daniels to alleviate the somewhat itching contradiction that existed in the early inspirations of Everything, when the duo went to see a ‘90s double feature

a few years back. “It was The Matrix and Fight Club, and it was at the New Beverly, and I fell in love again with those movies,” Kwan recalls. “I was like, man, if I could just make something half as fun as The Matrix is, but with our own stamp and our spirits, I would just die happy.”

Kwan remembers being inspired specifically by The Matrix’s iconic fighting scenes, which harkened back to Daniels’ shared love of kung-fu films. The distinction, Kwan notes, is that “we don’t love violence, but we love action movies.”

“There’s something so entertaining and visceral about it, and we wanted to try to take that kind of energy and satisfying filmmaking and point it towards love and understanding,” Kwan continues. “Which was another fun challenge that we were like, we don’t know how to do that, but we want to see it on the big screen.”

Inspirations, writing, and development

“I was sitting there going: Nah, no one in their right frame of mine is gonna do something like that with hot dog fingers,” Michelle Yeoh says.

She’s remembering the first time she read the script for Everything Everywhere All At Once, an early view into where Daniels would take her on their multiverse fever dream including, indeed, a world in which she would have hot dogs for fingers and use them in decidedly unusual, strangely poignant ways with Jamie Lee Curtis. Yeoh hadn’t seen Swiss Army Man yet, but had heard good things—perhaps if she had watched that movie, starring Daniel Radcliffe as a flatulent corpse who provides companionship, survival tools, and a glimpse of transcendence for Paul Dano, she might have had a better sense of what she was getting into.

It was, in fact, on the press tour for Swiss Army Man that the co-directors were really sold on their then-fledgling idea of a sci-fi multiverse movie, after landing on the intriguing concept of going, as Scheinert puts it, “existential nihilism nightmare town” on it. But in between would be the hot dog fingers, along with the colorful tangle of ideas and locales that would come with a Daniels film that explored the infinitude of possible lives.

“We wrote a draft and everybody was like, this sounds like a $100 million movie, you’re gonna have to rewrite this, guys,” Scheinert says.

Nevertheless, thanks to their experience in music videos, a field where they learned to create immersive worlds on tight budgets and on computers in their bedrooms, the duo, along with the help of a small, trustworthy crew of friends they’ve worked with for years made a work that doesn’t sacrifice the expansiveness or wildness of a nine-figure idea.

“The creative tension in our partnership usually comes from me being way too ambitious and him being very cautious of efficiency and cost-effectiveness,” Kwan says. “And that struggle and that tension focuses us so that we spend the money where it really matters, and everywhere else we try to skim, skim, skim and compromise.”

Or, put another way: “Dan has a maximalist aesthetic,” Scheinert says. “Sometimes his ideas will be these kind of run-on sentence ideas. Like, they say this! And then this happens! And then my job is to just cheerlead.” And together the duo find a way to make the run-on sentences into feasible creations.

For both of them, the balls-to-the-walls ethos that is a hallmark of their work comes from their early days of creating stuff during the initial waves of Internet content. While Everything offers a treasure hunt of eclectic cinematic references—from 2001: A Space Odyssey to In the Mood For Love to Ratatouille—Kwan insists their voice is far from that of a cinephile, but was honed rather through things like YouTube videos, “Tim and Eric” sketches, and the form-breaking anarchy of Japanese anime movies.

“We would put our stuff online, and the algorithm would push it because it was so insane, and then we’d get attention and that positive reinforcement,” Kwan recalls. “We were like, oh, I guess we should be more insane.”

That feedback, though, threatened at one point to pull them down a rabbit hole of making films that were starting to feel emptily unhinged. “That self-consciousness that we felt, this feeling of wasting our lives, forced us to try to cram something personal into our work, just to see what would happen,” Kwan said. “It was this really weird synergy of us collaborating with the algorithm. The algorithm told us: go big, poke through make weird stuff. And then our hearts were like, but I want

to share something that is meaningful—how do we do that?”

The high-wire achievement of Everything is precisely in embodying this unwieldy tone. The almost schizophrenic imagination that Evelyn falls into causes the film to build towards a conclusion that is surprisingly cathartic; Evelyn’s journey through all of her possible lives helps her understand what matters most in her own. “One of our favorite things to do is make people feel emotional while looking at something that is absurd,” Scheinert says. “Whenever we can pull that off it’s just like, oh, what a fun feeling! We feel emotion, but we also feel this kind of mischievous joke has been pulled.”

That would include scenes that required Curtis and Yeoh to have ketchup and mustard squirted into their mouths and down their faces. “We kept saying, ‘it’s going to be like a beautiful, emotional part of the movie,’ and they were like, ‘what on earth are you talking about?’” Scheinert recalls. “And when we finally edited that together, I was like, ‘yes, we were right!’”

In Everything, the personal, human core was partly borne out of Daniels’ conversations about their own mothers and the difficulty of generational divides, a universal experience that has been dramatically enhanced by the onrush of the digital age.

Kwan explains, “In the end, this character resembles my mom more—the kind of flustered, overwhelmed mother who is doing a million things at once, and never really doing any of them with full focus.”

The pair initially conceptualized Evelyn as a woman with undiagnosed ADHD, a condition that in a way makes her uniquely equipped to tap into other universes. But, worried about treating the diagnosis reductively, Kwan started looking into it more deeply and was led to a startling revelation: “I basically stayed up until like four in the morning just researching. I was like ‘Oh no, oh no, what the hell,’” Kwan says. “Because it never crossed my mind that I could have ADHD.”

He would eventually be officially diagnosed after spending a year with a therapist, suddenly giving him, in his 30s, a new understanding of his brain and his struggles as a child. It also offered a new way of seeing both his own mother and Evelyn.

“That is a big part of what makes Evelyn feel so unique and alive, the fact that she has this thing—that I relate to and that I felt for most of my life—this overwhelming feeling of wanting to do so much, but then not being able to do any of it,” Kwan says.

In the film, Evelyn becomes a Neo-like chosen one specifically because she is the single-most failed version of all her potential selves. “That gives her superpowers to be able to defeat the bad guy,” Kwan says. “But,” Scheinert notes, “mostly she gets distracted by all these lives that she wished she had led.”

It is also possible to see Evelyn’s many lives as an allegory for the immigrant mother: appealing paths suddenly walled off, like alternate selves, when you leave your home—the new roads you’ve been promised in a land ostensibly rife with opportunity reveal themselves to be largely inaccessible. “For her, the journey has not been easy,” Yeoh says. “She made a choice to leave her own family in China and set up a new life with a man that she loves, and wants to have a fresh start, but things do not always go according to plan.”

That experience makes the feelings of the next generation, who grow up and live a life of relative stability in a country they feel is innately their home, practically illegible to a mother like her. “Both my parents immigrated here,” Kwan says. “When you’re just integrating here, you don’t have the time or the luxury to think about anything other than survival.”

He references a line from Mike Mills’ Beginners: “Our good fortune allowed us to feel a sadness that our parents didn’t have time for, and a happiness that I never saw with them.” When you add in the internet and its seismic cultural shifts, a daughter whose life as a queer person is incomprehensible to her parents, and an aging father, the generational divides in the family further splinter and spread.

In this sense, it is perfectly apt that Evelyn’s daughter, Joy, is also the multiverse’s villain, Jobu Tupaki—an agent of chaos that is both the thing to defeat and perhaps to save. “Jobu is a manifestation of that kind of weird generation gap, and the multiverse can play as a really funny metaphor for just the Internet,” Kwan says. “The emergence of the Internet was something we grew up on, and it totally affected us and f***ed us all up and now we are the way we are, and our parents are trying to play catch up.”

In 2022, in an era of information overload, extreme polarization, and mass existential dread, the struggle to connect between parents and children might feel less like a banal, everyday experience, and more of an increasingly confounding battle between a loved companion and a mortal enemy. “In a lot of ways, the movie is just a family drama,” Scheinert says, “and then we came up with some of the most insane, enormous, overcomplicated hyperbolic metaphors for generational gaps, along with communication errors and ideological differences within a family.

Casting Everything

In one of their alternate universes, Daniels would have made a version of this movie with Jackie Chan as its star. That was one of the early, somewhat cockeyed schemes the co-directors had for what became Everything Everywhere All At Once.

For various reasons that one might expect when it comes to pinning down Jackie Chan, that dream was dashed, but, as they returned to the script, something clicked—it allowed Everything to become something entirely new, making way for a late-career revelation for Michelle Yeoh.

“It really felt like the script came alive when it became about the mom and it was Michelle as the lead,” says Scheinert. “That got real scary because we literally couldn’t think of anyone else if she said no. Or if we found out that Michelle Yeoh is a terrible person, then the movie dies.”

That fear was readily apparent to Yeoh, who it turned out, was not a terrible person, but more of a lovingly exacting mother who refers to the co-directors as “the boys.” “I remember meeting them—they can be very over-the-top when you get to know them better—but at the beginning, they’re kind of shy,” Yeoh recalls of their first encounter. “They were maybe a little intimidated. I seem to be such an intimidating figure. I’m like Eleanor Young walking around, saying, ‘You’ll never be

enough!’”

She’s jokingly referencing her character, the imperious matriarch from Crazy Rich Asians, which would become a smash hit just months after Yeoh first met Daniels (and helped ease Daniels’ anxiety about Hollywood’s willingness to make a film centered on a Chinese family). And indeed, that is perhaps how the industry itself has seen her for years.

“I’m always sort of cast into the more serious role,” Yeoh says.

“You know, the one that brings the sanity back into your life and makes you understand what is important, what’s deep and wonderful, and blah, blah, blah.”

“I think it’s one of the things where no one has asked her to do anything but that, because a person gets typecast or whatever,” Kwan says. It’s hard for anyone to shake off the idea of Yeoh as this sort

of towering, regal figure. “Her assistant with whom she’s worked for years and years was very upset the first few days of shooting,” Kwan recalls. “She was like, ‘You can’t make her look like that. That’s not what Michelle looks like. Don’t do that! Take that wig off her head, she doesn’t have gray hairs!’”

In Everything, Yeoh is unkempt, emotionally flayed, and put through the multiversal ringer in a role that is entirely singular within a prolific, decades-long international career. And she knows it. “On Friday nights we’d all go back to her hotel room because she loves to party and Ke [Huy Quan, who plays Evelyn’s husband, Waymond] loves to party,” Kwan recollects.

“They just want to drink and talk—like, all night—and one of the things she said to me that I was really moved by was: ‘I wonder what my career would have looked like if I had done this movie a long time ago.’”

Daniels offered Yeoh a new way to see herself on-screen. “I love working with younger directors because they don’t see you in the conventional way,” Yeoh says. “They want to peel that onion and see what other layers there are, and then start throwing crazy things at you.”

It helps, also, to shed your esteemed facade and lean in when you’re joined by a star like Jamie Lee Curtis doing a similar thing. Curtis, who also fully engaged in a shabby, strippeddown part as a glowering, sometimes unhinged IRS agent, became a bit of a gang with Yeoh. Curtis remarks, “The truth of the matter is, had they just said, ‘There’s a Michelle Yeoh movie that they would like you to be in,’ I would’ve said, ‘Okay.’”

“The first thing she said to me was, ‘If you don’t like the boys, we can run away. We can elope together,’” Yeoh says with a laugh. Together, the pair would playfully tease Daniels, and entered spaces of vulnerability at times hand-in-hand. “Sometimes, Michelle, as brave as she was, had some hesitancy, and when Jamie was there, she would do anything,” Kwan says.

“It was this really beautiful thing where they were like, I don’t know what we’re doing, but we’re doing it together.”

Yet, while Curtis and Yeoh—along with the 92-year-old legend, James Hong, who was so perfect for the role of Evelyn’s father that nobody else even auditioned—made for a pair of veterans embarking on new horizons, their co-stars came from entirely different acting histories. The role of Waymond—a distinct part that ping-pongs between a soft-hearted husband and, in his multiverse persona, heroic action star—marks the show-stopping return of Ke Huy Quan, who nostalgic viewers might remember as the man who was once Short-Round in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Data in The Goonies.

Even after portraying two of the most iconic roles of the ‘80s, Quan struggled to find work as a young Asian actor. He eventually went to film school at USC and largely stayed behind the camera—doing fight choreography and even working as an assistant director on Wong Kar-wai’s 2046—but ultimately left Hollywood for decades. It wasn’t, ironically, until he watched Crazy Rich Asians that he considered the possibility of a return.

“I saw that movie and I told myself, if you ever wanted to get back into acting, now would be the time, because times have changed,” Quan recalls. Soon after, he asked his friend to be his agent, and “a week later we got a call to audition for this,” he says. “The timing was just impeccable. And I was super nervous because I haven’t auditioned for over 25 years.”

The audition came, as unlikely as it sounds, from Kwan stumbling across a reference to Quan on the internet, wondering where the kid from Temple of Doom and The Goonies had gone, and sending out an ask almost on a lark. When he auditioned, he was “this ball of sweet energy,” Scheinert says, a perfect mold of Waymond. It also helped that he floored them with his acting, looked the right age, was bilingual, and knew martial arts. But, Scheinert notes, he also earned the part with the hard work that is required of his intense, shape-shifting, and stunt-heavy role. (In a rather charming full-circle moment, Jeff Cohen—a lawyer who, in middle school, played Chunk in The Goonies—did Quan’s deal for the film.)

Yet, if Quan was just returning to the spotlight, Everything provided the first big one for Stephanie Hsu in the role of Evelyn’s daughter, Joy. Daniels met Hsu on an episode they directed of “Awkwafina is Nora From Queens,” and Hsu developed a particular and immediate kinship with the them, inspiring them to mold the part for her.

“We rewrote it based on her sense of humor and just how weird she is, which is always such a gift, as a filmmaker—to just be like, oh, you’re going to inspire me now,” Scheinert says. Kwan adds, “She just has so much range, and I think she’s going to be huge.”

Hsu was able to tap into the role partly because the specific dynamic of the central Wang trio—a global star in Yeoh, a former child actor in Quan, and a breakout newcomer in Hsu—contained a kind of chemistry that mirrored their own characters. “Evelyn is really strong, determined, and the sort of mother who is keeping the ship afloat—or so she thinks— and offscreen Michelle is steadfast, but also so silly and loving and just a complete joy and blast to be around,” Hsu says. “My

experience of Waymond is always dad, and Ke is similar in that way where I don’t think I’ve ever met someone as sweet as him.”

Most of all, though, the cast were enabled by the loving, open on-set environment created by the filmmakers, who aim to run their productions like “summer camps” (which includes a morning circle that involves a new improvised game every day, like Hsu’s own “Hug Tackle”). “It’s very intentional the way that everyone is cultivating a workspace and a creative environment that is full of joy and kindness,” Hsu said.

Daniels point to two instances that established the familial ethos for the production, one involving a bonding experience from a script breakdown, in which Yeoh and Quan, baffled by the stiff translations of the Chinese dialogue, helped retranslate lines. The other was an early cast and crew Korean BBQ night. “Ke was like ‘I’ve never done sake-bombs, let’s do sake bombs!’” Scheinert says. “He bullied James Hong into doing sake-bombs.

“A 90-year old man!” Kwan says. “And he was down.”

Behind the scenes

“You know the two guys who have the trophies up their butts?” Daniel Kwan asks. That would be Andy and Brian Le, brothers and fight choreographers who make brief, sometimes painful cameos as henchmen, and who—overseen by stunt coordinator Timothy Eulich—helped shape the distinct fighting style that the Daniels wanted from the action scenes in Everything: less of the bruising grit of most Hollywood action, more of the loose, playful ethos of Hong Kong-style fighting, in which

Yeoh first made a name.

The style, Eulich explains, “offered us an opportunity to create stylized, character-driven action with balletic fights and wire-assisted stunts that you just don’t see in movies today.

That spectrum of cinematic violence juxtaposed with Daniels’ humor made for some distinctly unique stunts and action that you’re not going to see anywhere else.” But it was also crucial in giving the film’s many action scenes narrative direction and thrust. “For this type of movie, with its

wackiness,” Andy Le says, “the realism of modern-day action wouldn’t fit too well. With Hong Kong action, you can go as wild as you want and it will fit the tone of the movie, it will push the story forward…”

As CGI has gotten cheaper and more accessible over the last two decades, and superhero movies have proliferated, it has become something of a cliché to destroy a major American city in the course of a fight scene. Which makes the grounded, relentlessly surprising fights in Everything all the more distinctive: the environment and props feel as much a part of the action as fists and feet, with a fanny pack and a perverse range of office supplies recruited as weapons.

The scope of Everything, though, feels no more limited as a result. This is partially a credit to the small crew of visual effects superstars that the Daniels worked alongside of, but also due to the film’s distinct look and style: while blockbusters require hundreds of people on an effects team to create a highly photorealistic look, Kwan and Scheinert relied on a team of about eight to create a vision that is goofy, singular, and uniquely immersive.

The expansive quality also comes back in part to the conceit of the film itself—the act of verse-jumping meant being able to play with a pastiche of genres, visual palettes and even cinematic odes (like what the Daniels call the “Wong Kar-wai universe”). The film often straps the audience into a rollercoaster ride of sorts, with sequences and montages that race through universes that can each feel like their own movie.

“When we would jump from thriller to action film to comedy and back to family drama with a quick stop in 40s noir, we had to make sure that the audience was sure-footed in each experience,” says the film’s editor Paul Rogers. “So knowing the tropes and tones that we were aiming for helped us to really land the audience in each world with confidence. I don’t think it would have been successful if the film felt like a mushy mashup of genres.”

Perhaps the biggest boon to crafting a tangible multiverse was the production’s primary shooting location: an old office building in Simi Valley, formerly the home of a predatory loan mega-corporation that had been turned into a massive, rentable shooting warehouse where the production team built most of the sets and created what production designer Jason Kisvarday refers to as a cost-effective “playground” for their movie.

“There was a lot of weird energy in there. It’s a sprawling building—lots of corridors, basement spaces, conference rooms, a giant open cafeteria, and that atrium in the middle. It’s incredible,” Kisvarday says. “It was big enough that we could wreck one part of the building, then walk away and just go somewhere else in the complex to continue filming while our team restored the initial part of the building.”

There, Kivarsday was able to create a carousel of sets that could feel grounded, such as the Wang family apartment, before what he calls “magical realism” suddenly transformed the visual space (such as when a drab, open-office IRS workspace becomes an intergalactic battleground). Working in the distinct office warehouse, though, also helped inspire the birth of completely new universes.

“Entire sequences were written around the unique geography and architecture in that building,” Kivarsday says. “Sometimes we really wanted to get weird and create a vibe from scratch. Example: Hot Dog Universe.”

The other crucial through-line for the multiverse would be the film’s maximalist score, by the shapeshifting Los Angeles-based band Son Lux, composed of keyboardist and vocalist Ryan Lott, guitarist Rafiq Bhatia, and drummer Ian Chang. Tasked by the directors, according to Lott, to “do all

the things, but make it feel like one thing,” the trio was brought on before production to begin a collaborative, freewheeling process to find the sound of the multiverse.

“We sent a ton of musical ideas and other sonic materials before they started shooting, like examples of customized instruments we built virtually with the film and its many universes in mind,” Bhatia explains. As the movie was coming together in the edit—much of it cut with temp music sourced from earlier Son Lux recordings and band members’ solo projects—they were able to have a unique back-and-forth with Daniels, Bhatia continues, “between the music and the edit, in such a way that each aspect could build on—and up the ante for—the other.”

Kindness in the chaos

These days, Kwan says, much of art is broadly struggling to confront two things: “One is this feeling of everything happening all at once—how can you put that in a story in a way that is meaningful? And the other is climate change.”

Everything Everywhere All At Once is most obviously Daniels’ attempt at trying to encapsulate the first part, but you can sense the latter lurking in background as well. Of course, in Daniels’ language, if climate dread is an inspiration, it takes on a decidedly different look: in Jobu’s evil plan, an everything bagel-void threatens to swallow the multiverse and destroy us all. “This project came out of our own anxieties about living in the modern world, and I think everyone I know is trying to

capture that,” Kwan says.

The feeling was already there when they were writing it in 2016, before the Trump Era and the pandemic. “We already felt overwhelmed. And, and as we were writing it, we were like, ‘Oh my God, what is happening? It’s getting worse—how could it possibly get worse than this?’” Kwan says. “Everyone is trying to process that feeling, the backdrop of doom, the backdrop of chaos.”

Daniels doesn’t have a grand answer to a radical new path, but Everything at the very least offers a simple hope in response to the chaos. “One of the most powerful things you can do for someone is to pay attention to them,” Kwan says.

For Evelyn, she has to confront a multiverse on the brink of collapse—an extreme manifestation of the sensory overload that the modern world is increasingly defined by—to see the family that has always been there. “You have to go to the end of the world to find out what really matters to you: your daughter, your husband—would you make another choice?” Yeoh ponders.

It’s a question and a reminder of sorts for the audience, too: to see what’s in front of you, to reach out, to be kind. That’s what the film became in part for the Daniels themselves. “I would love if audience members take away the idea that kindness can be a powerful way to fight. I think telling this story definitely made us reflect on the idea that,” Scheinert says, slipping into a Bill and Ted voice, “like, ‘Oh yeah, kindness— sick!”

Have you seen the movie? What did you think? Let me know in the comments or on social.